As I mentioned in a recent Fontenotes, my parents both went on Hospice in March. In the ensuing months, we have had many talks about dying and all the physical, emotional and financial needs that surround this last stage of life.

As I mentioned in a recent Fontenotes, my parents both went on Hospice in March. In the ensuing months, we have had many talks about dying and all the physical, emotional and financial needs that surround this last stage of life.

My parents are exceptional. I mean that beyond my view as one of their four kids; from any perspective they are unusual. Mom (93) and Dad (96) live independently in a lovely retirement center in Providence RI, have fully functioning minds if not bodies, and are actively involved with their family and the world (negotiating turns with the New York Times is the closest they come to a sport these days).

They also offer a unique insight into what it is like to be facing death so imminently. Mom is a nurse involved in social justice issues all her life; Dad is a retired physician (Hematology-Oncology) and medical academic (teaching at Harvard and UCONN Medical Schools).

I thought I should interview them about what it feels like to be dying. As Mom has stabilized and is significantly the healthier of the two, we have decided to complete her interview down the road. I dedicate this Fontenotes to messages from my Dad.

A Bit About my Dad

My Dad is a physician (Harvard ’46) who published extensively over the years in the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, and many periodicals devoted to medical science, hospital administration, and public health.

His 1974 book “The American Health Care System: Its Genesis and Trajectory” served as an academic text at numerous universities for years. Dad was the General Director of the two hospitals in Boston that he brought together to ultimately become the “Women’s” part of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital merger and was the Educational Director at Hartford Hospital from 1969 until 1975.

I am telling you all this to illustrate that my Dad is a doctor’s doctor. I was raised hearing not only about the importance of medicine to save people and communities, but also the importance of maintaining professionalism to save medicine.

Talking to Dad

We want to start with a caveat that pain does not complicate our conversation about dying; although his cancer is advanced, and his bone metastases are multiple, he amazingly, thankfully is comfortable right now.

Even so, anyone entering a conversation entitled “What’s It Like to be Dying” would undoubtedly anticipate messages both profound as well as sad. Heaven knows my Dad is always profound- but he is not, surprisingly, very sad these days.

His #1 complaint is boredom.

With a sound mind, my Dad has a body that will do increasingly less. His level of activity outside of his home is foiled by failing strength, breath, and ability to accommodate all his needs in the outside world. More and more he is a prisoner in his home, and in his mind.

If he were a man of faith, he would presumably be having long conversations with his spiritual advisor- but he is not. Death is an intellectual exercise, not a transformational one.

Now sitting waiting for death is, ultimately, boring.

He tells stories (with jealousy) of friends who died suddenly or in their sleep. “All I want is a great heart attack.”

Waiting for his cancer or failing organ systems to ultimately provide him “escape” (and that is his word) is long, tiring and tedious.

Please Call it Dying

Amid all that waiting and boredom, Dad finds it frustrating that people can’t talk comfortably about death and dying with him. They don’t even use those words.

Mom & Dad have extensive conversations about their limited future; more importantly, about their past. In his family, all of us are ready to meet his death, and everything along the way, with him head-on.

But beyond his home? The world has multiple ways to express the sorrow of his “passing,” but not for the dying he is in the process of right now.

“Death and Dying are perfectly good Anglo Saxon words!” he proclaims with a booming voice that would resonate with all who have ever known him. “Don’t use euphemisms- they mean nothing!”

In truth it is not the words per se that bother Dad- it is the pervasive discomfort people have to talk about death with him at all.

Here is the bottom line for my Dad. Dying in a world where people won’t talk about death is lonely.

Talking about Death with His Fellow Physicians

Dad’s yearning for people who are open and relaxed talking to him about dying is particularly acute when he talks about his current physicians. None of his doctors will have a frank conversation about dying with him. “I just want to know what it will be like, I just want a doctor I can talk to.”

Interestingly, his plea is not a complaint that modern doctors should be better at shepherding their patients toward death. Far from it.

When I asked, “Would it have been better if you were dying back in the days of your training?” “Heavens No!” he thunders. “It was anathema even to mention that your patient might die back then!”

He thinks medicine has come a long way toward increasing its value in end-of-life care since his own glory days.

More to the point- my Dad is not sure society’s demands on physicians, or his anger at them, is justified. “Doctors are trained to keep people alive. I am not sure it is fair to now ask them to be experts at helping their patients die.”

Even so- as a physician- he wishes he could get more from his own.

I Want to Die

Perhaps the most significant puzzlement Dad has is why people don’t understand why he wants to die, sooner (and suddenly) if possible.

Is he depressed? No.

Does he hate the thought of leaving Mom alone after 67 years? Absolutely. Does he get choked up saying farewell to each of us, his loved ones? More than I can describe.

But he wants to distinguish that emotion from being sad about dying.

Most nights my parents close the day with a cocktail. Every time they do so, for decades now, they greet each other eye-to-eye, hold their glasses up and say “Abbastanza.”

It is a word they learned on one of the countless trips they took in younger years; this one to Italy. Abbastanza means “enough.” It has been their toast all these years to each other: enough love, enough adventure, enough time to be together and a family. It is a toast of infinite gratitude.

Now that he knows he won’t fully be Jeff Freymann much longer, Dad wants to die while all of that is still true; is still the predominant feeling he has about his life.

“Abbastanza” and “I want to die” are synonymous for my Dad.

Messages

Dad and I did not set out with a specific purpose or thought about what any reader would glean from this very personal Fontenotes.

However, we hope it leaves you with a thought, some solace, or a view of death different from- an addition to- your own concepts or concerns about dying.

Most of all, we thought when the time arises it might be a stepping stone to have your own conversations with your loved ones in your own way.

If that is you- start talking. Being open is the hard part, it will get easier along the way. We promise.

In closing, I want to thank my Dad for once again so generously sharing his thoughts, as he always has and will until his last breath.

About the Pictures:

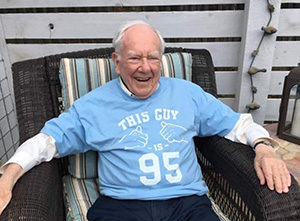

The portrait of Dad is from his 95th birthday, the other is what I see when I sit at my desk. It captures perfectly who my dad has been for me as a professional woman.

He opened my eyes to the world of medicine but supported me wholeheartedly in my chosen paths of nursing and law. We have dived together into the most difficult ethical issues in medicine; we have spent hours talking about our shared passion for the future of health care.

Since the time I first started thinking “what do I want to be when I grow up,” he has been my teacher, my sparring partner, and my champion. He still is. Dad will leave a hole not only in my heart- but in my brain and thought process. All of me will miss him dearly.