When asked if I recommend traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage (formerly called Medicare Choice), my answer is swift and definitive.

Traditional Medicare is by far the better option.

There are five reasons I warn people away from Medicare Advantage plans:

- If you get injured or sick, coverage for your care will be subject to standard insurance practices (such as preauthorization) and will more likely be delayed and/or limited;

- Medicare Advantage Plans have fewer participating physicians and are less likely to cover care from your preferred medical team;

- Delays in payment from Medicare Advantage plans are hurting hospitals, especially in rural America;

- There is a lot of fraud in billing for MA plans. For example, in January, Kaiser exposed “90 previously secret government audits [2011 to 2013] that reveal millions of dollars in overpayments to Medicare Advantage health plans for seniors.”

- Medicare Advantage does not save money as envisioned when President Clinton announced “Medicare Choice” (Medicare Part C) in 1997. For many years it cost taxpayers more money per beneficiary to keep a person on Medicare Advantage than the monthly federal cost for traditional Medicare. To add insult to injury, of those costs under Medicare Part C, a percentage of those federal funds wind up in the pockets of shareholders of private insurance companies instead of paying for care for the patients in their plans.

In Part II of this series, I will give you data to support each of these complaints, with links for you to do your own research.

However, to explain all the above, I must first detangle the components of traditional Medicare and explain how Medicare Advantage, at face value, appears to be an easier, more attractive choice. The marketing is deliberate and successful. But what are you actually buying?

Explaining Traditional Medicine

Medicare is famously confusing (don’t miss the great cartoons here!). It is complicated because it contains many segments (Parts A, B, C & D) that require separate payments. The easiest way to make the structure understandable is to start at the beginning.

President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law in 1965 to protect “elderly Americans” (i.e., those over 65) from the “hopeless despair” of not being able to afford health care. (The same law also created Medicaid; for the differences and an easy tip to remember which is which see Fontenotes No. 48.)

When it was created, Medicare had two parts:

Part A: Provided automatically to most people on their 65th birthday (to see more about eligibility and who can get Medicare at an earlier age, go here), Medicare Part A pays for inpatient hospital care, critical access care, short-term care in skilled nursing facilities, inpatient mental health care in a psychiatric hospital (limited to 190 days in a lifetime), hospice, and some home health care.

Medicare A does not pay for you to be in an assisted-living facility, long-term nursing home, or custodial care (such as assistance with bathing, dressing, making meals, and other activities of daily living). It also doesn’t pay for your physicians and other health care team members. (For more on the harsh financial realities of end-of-life care, see Fontenotes No. 62.)

Medicare Part A is “free” if you (or your spouse) paid sufficient Medicare taxes during your working years. More information is available from CMS here.

Very few people only enroll in Medicare Part A (7.5% in 2019); these people are predominantly people still working with additional insurance through their employers.

Part B: Medicare Part B is optional coverage to help pay for visits to your physician or other providers, outpatient care at the hospital, some preventive services such as tests and screenings, physician services while you are in a hospital (usually 80%), physical and occupational therapy, and some home health care.

If you opt for Medicare Part B, the premium is deducted automatically every month from your Social Security check ($164.90 for most people in 2023, with variation depending on the modified adjusted gross income you reported on your taxes two years prior).

Although it is technically voluntary, the vast majority of people who choose traditional Medicare opt for Part B coverage.

Supplemental Medicare Plans [“Medigap”]: The original Medicare framework does not cover all health care costs. Even with both Medicare A & B, a person is at risk for significant out-of-pocket expenses.

If you are hospitalized, the deductible for Part A is $1,600; the co-insurance is $400-$800 a day if you are hospitalized for more than 60 days; and Part B will only cover 80% (in most cases) of the fee for the doctors who take care of you (the remaining 20% can easily reach thousands of dollars). [For more on these additional costs, go here.]

Over time, these “gaps” in Medicare coverage (i.e., co-insurance, deductibles, and co-payments) were bridged by separate, private insurance policies called “Supplemental” (or “Medigap”) insurance, available to traditional Medicare beneficiaries for a monthly premium sent to the issuing company.

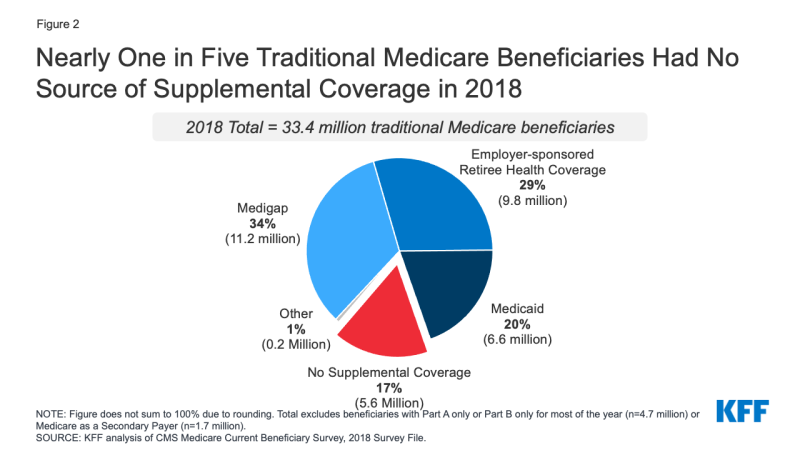

Although not part of the original Medicare design, all but 17% of traditional Medicare beneficiaries in 2018 had supplemental coverage through a Medigap policy or other resource. (As you will see in the diagram from Kaiser, Medicaid or retirement coverage from an employer provide supplemental coverage for many people.)

Part C: This section of Medicare is the Medicare Advantage alternative, which I will explain in detail in Part II of this Fontenotes series.

Part D: The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) created, for the first time, an optional avenue for drug coverage under Medicare. “In 2006, the first year of implementation, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that Part D participants will spend, on average, $792 out of pocket for prescription drugs (excluding premiums), which is 37% less than the $1,257 they would have spent in the absence of the law.” [quote] [Go here for an in-depth review of Medicare Part D by Kaiser in 2004.]

Medicare beneficiaries can choose from multiple Part D plans (all from private companies); the monthly cost depends on income and what prescriptions the beneficiary takes.

How Does Traditional Medicare Pay?

“Generally, Medicare covers services (like lab tests, surgeries, and doctor visits) and items (like wheelchairs and walkers) it considers “medically necessary” to treat a disease or condition… Medicare may cover some items and services only when you get them in certain settings or if you have certain conditions.” [quote, emphasis added] Once diagnosed (and documentation in your record supports care is “medically necessary”), obtaining treatment, surgery, a prescription, or other care without further appeals is standard for Traditional Medicare. (Please note that you may have expenses related to any of the above, but you must be notified in advance of any out-of-pocket costs.)

I have to add that from the provider side, this is a tremendous oversimplification. Health care providers spend enormous resources on understanding acceptable reimbursement codes and how to comply with Medicare requirements. Having said that, from the patient’s perspective, the care received essentially follows the care prescribed by the physician or the hospital treatment team.

Medicare Advantage is an Easier Choice

The explanation of traditional Medicare, at 879 words, is the shortest I could write.

This won’t surprise anyone who has approached 65; traditional Medicare is inordinately complicated.

Accessing coverage through Medicare is even more convoluted for some, especially those eligible not because of their age but because of a disability. [For more on this possibility and an explanation of enrollment periods, with potentially helpful downloads, see Original Medicare (Part A and B) Eligibility and Enrollment from CMS, available here.]

However, assuming you are (or will be) an average retiree, if you want to stick with the original plan, you need to understand (or pretend to understand) that you will be paying for your health care insurance four different ways:

Part A: You already paid this through years of work and taxes;

Part B: You will pay through a deduction from your Social Security check;

MediGap: You will purchase and pay monthly for a plan (unless you have supplemental coverage from another source, as demonstrated on the graph from Kaiser (above)

Part D: You will pay for the plan you pick with another monthly deductible to another private company.

Compared to that, selling a Medicare Advantage plan is easy.

Like traditional Medicare, under Medicare Advantage you don’t have to pay the Medicare Part A premium (depending on your work history).

Everyone has to pay for Part B (which may go higher or lower depending on your income); fortunately for Medicare Advantage Brokers, the Part B premium is deducted from your Social Security check, which may be less evident to the consumer (see above).

Most significantly, if you choose to opt into Medicare Advantage, you do not have to pick a Supplemental Plan or pharmaceutical coverage under Part D (most Advantage plans include prescription drug coverage). You have one monthly payment. Depending on where you live, that payment may be quite small, even zero dollars in some counties. (Hence the ads for “free” Medicare.”)

Even Better! Medicare Advantage plans usually include extra benefits such as vision, dental, and hearing coverage and will pay for your gym membership (“Silver Sneakers”).

It is no wonder why Medicare Advantage plans are becoming increasingly popular. They are easy to advertise; “Advantage plans that come with a zero-dollar monthly premium receive a lot of commercial airtime.” [quote]

But as attractive as the plan may sound when William Shatner, George Foreman, Jimmie Walker, Joe Namath (source), or superstars of tomorrow sell them- the devil is definitely in the details. Watch for Part II!

Want to Know More?

If all of this was a boring review for you- if you are a Medicare Expert- have fun and take the Medicare History quiz CMS has posted here!

An Addendum for Fontenotes No. 119

On May 26, 2022, I posted Fontenotes No 119: The Million Covid Deaths Aren’t Fake (available here). I still hold firm on my assertion that hospitals did not use Covid to increase reimbursement, especially after the rules changed six months into the pandemic. (Of course, there were bad actors on the side-lines that may have lied- but isn’t that always true; that is not the point)

What I do regret is not allowing for different schools of thought on counting those deaths.

In January, my eyes were opened by Dr. Leana S. Wren’s Opinion: We are over counting covid deaths and hospitalizations. That’s a problem [Washington Post 1/13/23, available here]

Dr. Wren received some harsh blowback from speaking up (look it up!), all the more reason why she deserves to be heard. I highly recommend you read her piece.